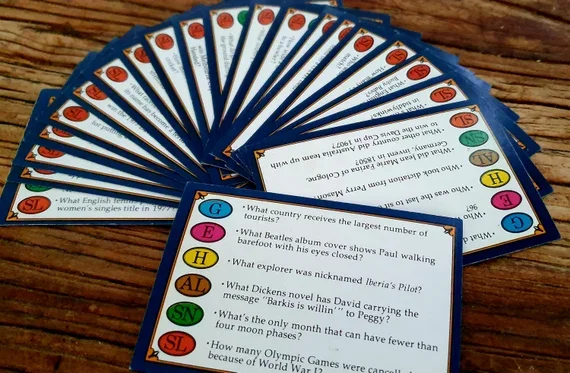

Trivial Pursuit is intellectual swagger in a box … Knowledge

as a competitive sport.

Don’t fight it — the wedge is genius.

Trivial Pursuit & Two Canadians

Who Rebooted Game Night

In 1979, the board-game industry was fading. Kids still played Candy Land and Life, but adults? They had moved on — to TV, to bars, to Atari, to anything but cardboard on a table.

Board games were becoming antiques.

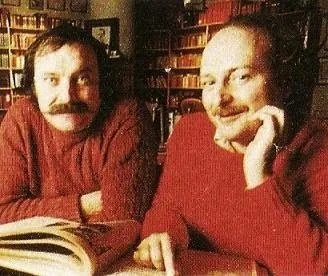

And then two broke Canadian newspapermen — Chris Haney, a photo editor, and Scott Abbott, a sports editor — changed everything in a single winter night.

They were playing Scrabble. A few tiles were missing. So they joked: “We should invent our own game.” That joke became Trivial Pursuit.

Haney and Abbott were living in a cramped Montreal flat, nearly broke, working long newsroom hours. But they loved trivia — bar quizzes, game shows, puzzles — and they knew a simple truth: Everyone knows something. Everyone loves proving it.

They scribbled the first six categories on a sheet of paper. They imagined question cards stacked endlessly. They envisioned a board where knowledge — not luck — moved you forward. By sunrise, the blueprint existed. A game designed not for kids, but for grownups.

The idea was brilliant. The industry thought it was doomed. Publishers rejected them. Retailers laughed. Investors said adults wouldn’t buy games.

Haney and Abbott did it anyway. They quit their jobs. Took on massive debt. Raised money from 34 tiny investors. Wrote 6,000 questions by hand. Used their press credentials to sneak into the Montreal Toy Fair, interviewing toy execs like undercover reporters.

Their first print run put them $250,000 in the hole. They kept going. Early adopters discovered it in bars and college apartments. People played it at parties, at midnight, with alcohol and arguments and laughter. By 1983, the wildfire had reached New York, Chicago, Toronto — and Parker Brothers finally bought in.

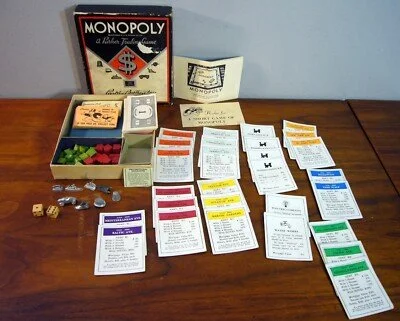

The result? 20 million copies sold in two years. The biggest board-game boom since Monopoly.

It didn’t just sell. It shifted the culture. Adults returned to the game table. Retailers expanded game aisles again. Party games exploded (Pictionary, Taboo, Balderdash). Licensing became a feeding frenzy. Expansion sets became a business model.

“Game Night” became a household phrase

Trivial Pursuit didn’t reinvent games. It reinvented players. It reminded the world that people don’t gather around a board for cardboard. They gather to laugh, to show off, to connect, to argue, to compete, to belong.

Haney and Abbott didn’t create a trivia game. They created a reason for adults to come back to the table. They rebooted Game Night — and every game that followed owes them a slice of the pie.

Marvin Glass didn’t just invent toys … He invented how toys are invented.

Same board. Different story.

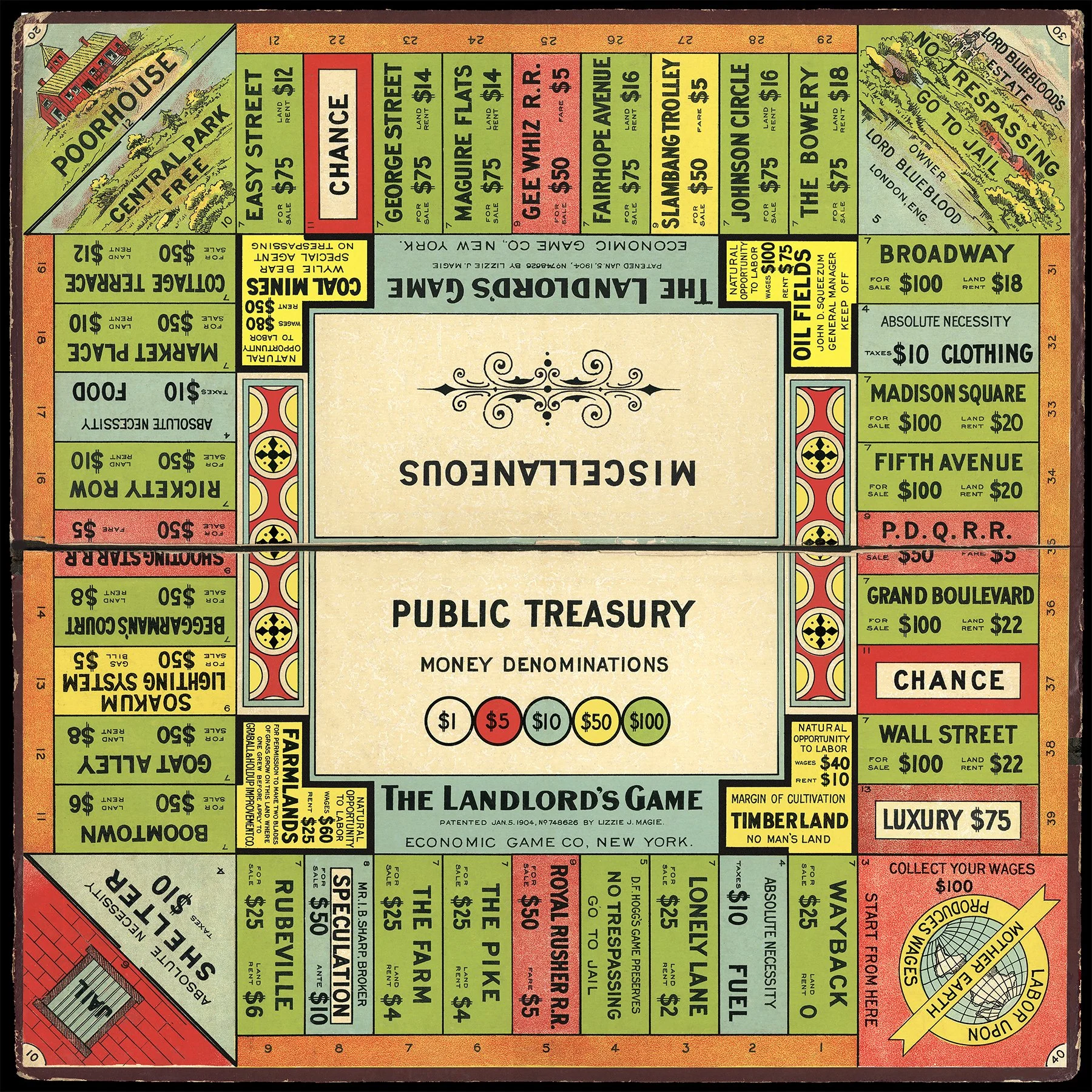

LEFT PANEL — The Landlord’s Game (1904)

Tone: Instructional, ethical, restrained

“Designed to show what happens.”

RIGHT PANEL — Monopoly (1935)

Tone: Bold, commercial, triumphant

“Marketed to celebrate it.”

WHAT MAKES THIS INVENTOR DIFFERENT

Designed a game as social criticism

Used play as persuasion

Predicted wealth inequality decades early

Lost control of her creation — to the very forces she critiqued

Marvin Glass & the Plastic Machine

That Changed Play Forever

During WWII, metal was rationed. That single constraint changed everything. Suddenly, novelty toymakers had to work with a new, cheap miracle material: Plastic.

Marvin Glass understood what that meant before almost anyone else: Plastic could turn imagination into mass production. But early in his career, he was mostly creating throwaway novelties — gag toys, knickknacks — quick laughs with no royalties attached.

His breakthrough fad, Yakkity Yak wind-up false teeth, became a national craze… and Glass earned almost nothing from it. That’s when the lightbulb went off.

Glass didn’t just change toys — he changed the industry.

Instead of manufacturing, he built a company that: Created ideas, Prototyped them, Licensed them, And demanded royalties. It was radical. Risk stayed with the big companies. Reward flowed back to the inventors.

Marvin Glass became the first true toy licensing empire, and soon every major company — Ideal, Milton Bradley, Hasbro — came knocking.

His workshop — in Chicago — became legendary: Concrete walls. Few windows. Steel doors. Security buzz-in. Everyone signed restrictive contracts. Every employee took a lie detector test

The creativity was wild.

The paranoia? Wilder.

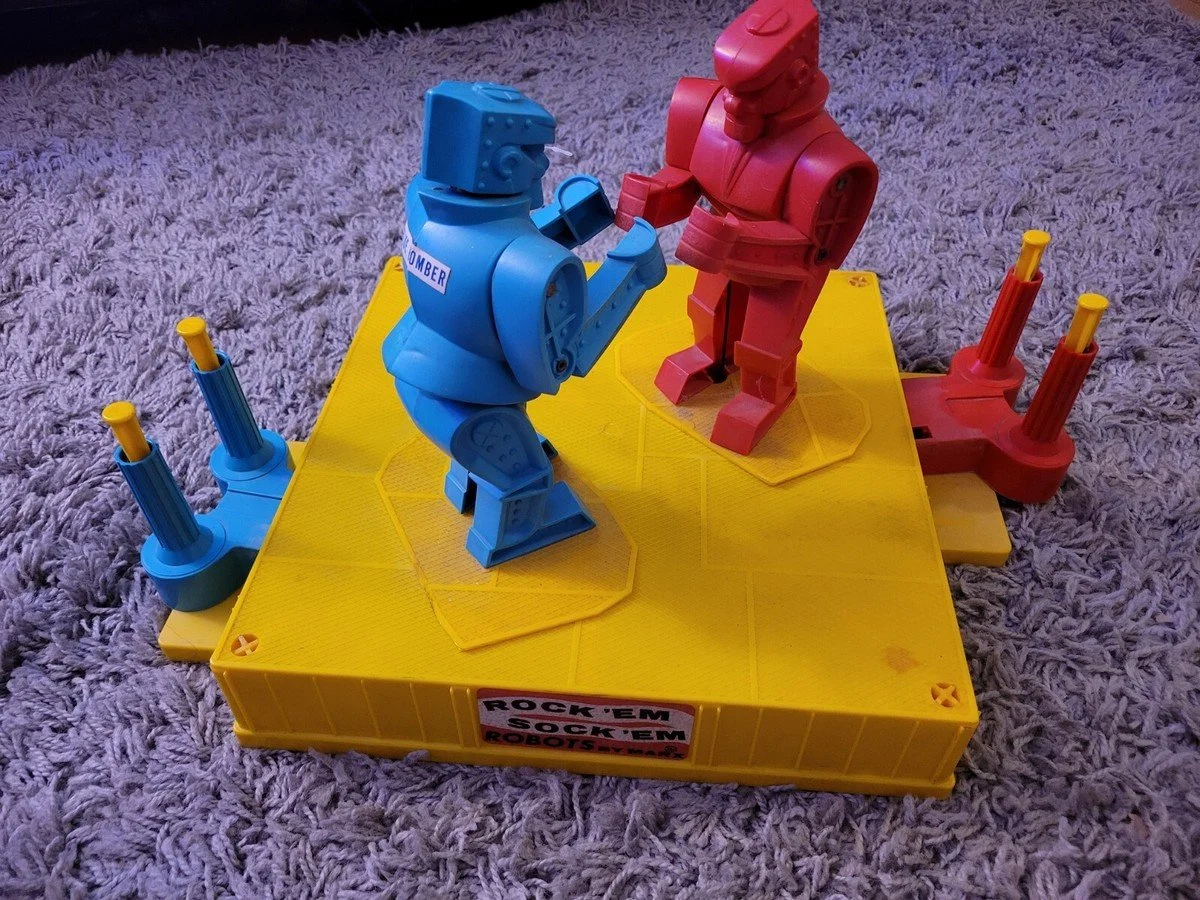

Glass was brilliant, manipulative, mercurial, and unstoppable. Ideas poured out of that bunker: Mousetrap, Rock ’Em Sock ’Em Robots, Operation, Lite-Brite, Mystery Date, Mr. Machine.

Some were chaotic misses. Some were cultural earthquakes. But the list is insane.

Not everyone thrived under the secrecy. One inventor — Dalia Verbakis — felt betrayed when Glass refused to give her proper credit for Lite-Brite. In retaliation, she secretly sold her own game, Feeley Meeley, to Milton Bradley behind his back.

She failed Glass’s lie-detector test — which he administered personally — and the betrayal cut deep.

This was the nature of the Glass workshop: Brilliance and resentment, side by side. Dreamers and schemers under one roof. Ideas passing through a meat grinder before reaching daylight.

Glass’s team was developing a serious boxing game — because boxing was HUGE and televised nationally. Then a real boxer died on live TV. The team panicked.

Glass pivoted instantly: “Dehumanize them. Make ’em robots.” Violence was still allowed — but now it was cartoon violence. A crisis became an icon.

Before Mousetrap, board games were: Wood, Paper, Cardboard, Flat, Simple. Nothing 3-D. Nothing plastic. Nothing truly spectacular. Mousetrap changed the rules. It wasn’t about deep strategy. It was about anticipation. Motion. Watching the machine do its absurd dance.

At first, toy execs hated it — “Too many pieces.” So Glass sent a prototype home with an Ideal Toys executive. The kids went insane over it. Eventually, 1.2 million copies sold in 1963, and a new era began.

Glass was often deeply in debt. He overspent. He gambled big. But he never cut the one thing he believed in: Idea people. He kept hiring inventors even when he couldn’t afford them. Because he knew: One idea — one plastic-powered spark — could pull the whole place back from ruin. And often, it did.

Marvin Glass didn’t just invent toys. He invented the modern imagination pipeline. He took the wild ideas living in sketches, workshops, and creative minds… and built the machine that turned them into everyday miracles on department-store shelves. He democratized wonder.

Monopoly & the Woman

Who Warned Us About It

tn the early 1900s, America loved games about progress — climbing ladders, collecting money, moving forward. But Lizzie Magie wasn’t interested in celebrating capitalism.

She wanted to expose it.

Magie was a writer, inventor, and outspoken critic of unchecked wealth concentration — deeply influenced by economist Henry George and his ideas about land ownership and inequality. At a time when women couldn’t vote and rarely patented anything, she designed a board game with a radical purpose: to show how monopolies crush everyone else.

She called it The Landlord’s Game.

The board looked familiar — properties, rent, money circulating in loops — but the message was sharp. As players acquired more land, others were slowly squeezed out. The game wasn’t about winning. It was about watching inequality happen in real time.

Magie patented the game in 1904.

It spread quietly. Teachers used it. Progressives played it. College students copied it by hand. Over the years, homemade versions popped up — rules tweaked, names changed, streets localized. Somewhere along the way, the warning softened. The satire faded. The cruelty became fun.

By the 1930s, a version of Magie’s game landed in the hands of Charles Darrow, who sold it to Parker Brothers as Monopoly. The company bought Magie’s patent for a modest sum, gave her little credit, and marketed the game as a celebration of ruthless success.

The irony is almost perfect.

The game designed to critique monopolies became the most famous monopoly of all.

Monopoly went on to sell hundreds of millions of copies, teaching generations of families how to bankrupt each other politely over kitchen tables. It became a cultural rite — part endurance test, part moral experiment. People didn’t love it because it was fair. They loved it because it revealed something uncomfortable about power, greed, and human nature.

And that was Magie’s point all along.

Lizzie Magie didn’t invent a family pastime. She invented a playable argument. A board game that smuggled economics into living rooms long before people were ready to talk about it. That her warning became entertainment doesn’t erase her achievement — it proves how effective the design was.

She belongs in the Board Game Inventors Hall of Fame not because Monopoly is beloved, but because it endures — still quietly teaching the lesson she tried to warn us about over a century ago.

Most inventors dream of success. Lizzie Magie designed a warning — and then watched it come true.